This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.ĭata Availability: All relevant data including individual participant data are available by request from the ClinEpiDB database ( ).įunding: The Etiology, Risk Factors, and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health and Development Project (MAL-ED) was carried out as a collaborative project supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation ( OPP1131125), the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center. Received: DecemAccepted: JPublished: August 17, 2020Ĭopyright: © 2020 Rogawski McQuade et al. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14(8):Įditor: Kawsar Talaat, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, UNITED STATES

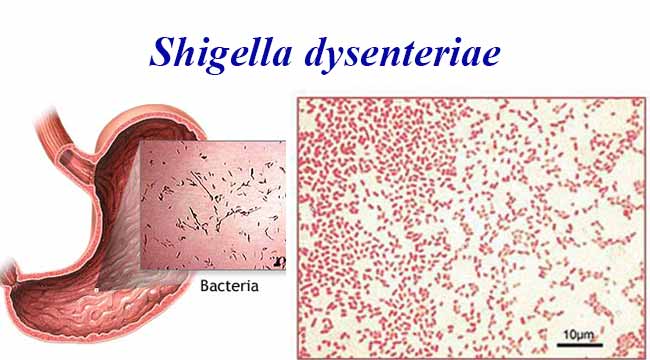

(2020) Epidemiology of Shigella infections and diarrhea in the first two years of life using culture-independent diagnostics in 8 low-resource settings.

Because culture missed most clinically relevant cases of severe diarrhea and dysentery, molecular diagnostics may be important tools in upcoming Shigella vaccine trials.Ĭitation: Rogawski McQuade ET, Shaheen F, Kabir F, Rizvi A, Platts-Mills JA, Aziz F, et al. There was a linear dose-response between Shigella quantity and myeloperoxidase, a marker of intestinal inflammation, which suggests a potential mechanism for the impact of Shigella on child growth. Older age, unimproved sanitation, low maternal education, initiating complementary foods before 3 months, and malnutrition were risk factors for Shigella. Shigella diarrhea episodes were more likely to be severe and less likely to be culture positive in younger children. The prevalence of Shigella varied from 4.9%-17.8% across sites, and the incidence of Shigella-attributable diarrhea was 31.8 cases (95% CI: 29.6, 34.2) per 100 child-years. We characterized the epidemiology of Shigella using highly sensitive diagnostic methods in 41,405 diarrheal and monthly non-diarrheal stools from the first two years of life in a multisite birth cohort. Shigella is the second leading cause of diarrhea morbidity and mortality among children in low and middle-income countries. Culture missed most clinically relevant cases of severe diarrhea and dysentery.

The burden of Shigella varied widely across sites, but uniformly increased through the second year of life and was associated with intestinal inflammation. There was a linear dose-response between Shigella quantity and myeloperoxidase concentrations. The sensitivity of culture compared to qPCR was 6.6% and increased to 27.8% in Shigella-attributable dysentery. The prevalence of Shigella varied from 4.9%-17.8% in non-diarrheal stools across sites, and the incidence of Shigella-attributable diarrhea was 31.8 cases (95% CI: 29.6, 34.2) per 100 child-years. To assess risk factors, clinical factors related to age and culture positivity, and associations with inflammatory biomarkers, we used log-binomial regression with generalized estimating equations. We tested 41,405 diarrheal and monthly non-diarrheal stools from 1,715 children for Shigella by quantitative PCR. We further characterized the epidemiology of Shigella in the first two years of life in a multisite birth cohort. Culture-independent diagnostics have revealed a larger burden of Shigella among children in low-resource settings than previously recognized.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)